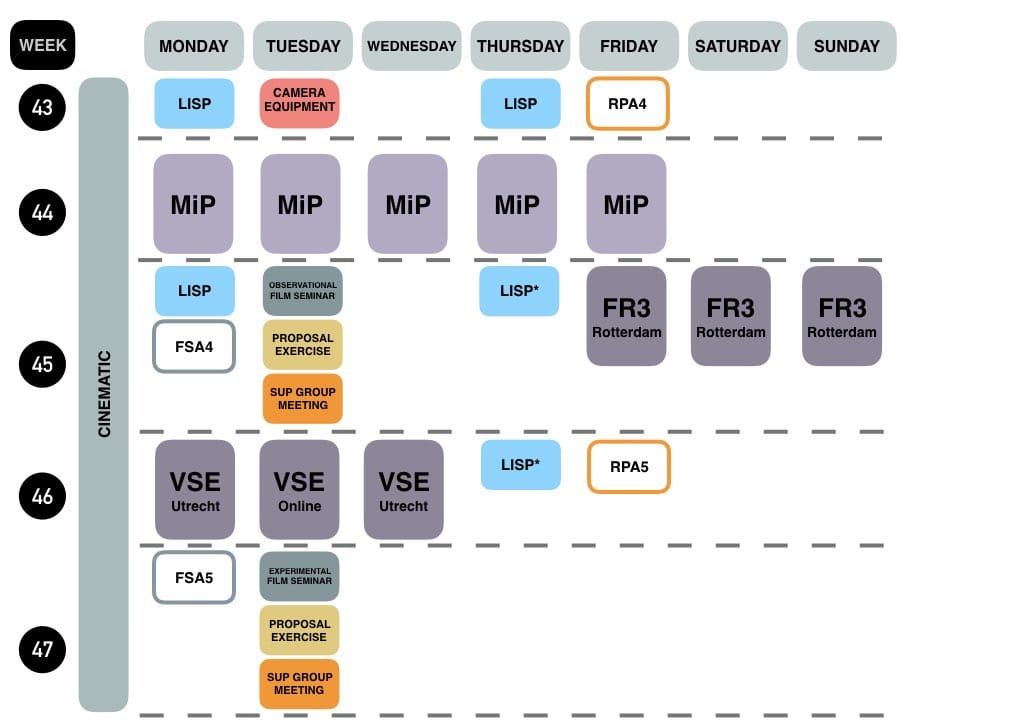

Cinematic Research Practices 14/10 – 17/11

When making ‘moving pictures’ became possible with the invention of cinema in 1895, a range of opportunities for its use opened up — primarily, the possibility to capture movement. When viewing the first film records ever made, we see endless scenes of ocean waves, flowers swaying in the wind, among other famous first records of human activities. Even before the Lumiere brothers, Thomas Edison and others began to amass huge archives of such scenes from all over the world. Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies had already transformed our conceptual understanding of human movement and animal locomotion.

At first the camera was too heavy to carry around and the hand-cranked machines needed to be mounted on a tripod to operate, showing the world from the perspective of a stationary ‘mechanical eye’. Once the camera became mobile, handheld camera-movement enabled cameras to move around and look at the world more closely to the way people do with a ‘human eye’. In our times, both the static and the moving camera have been engaged in a ‘dance’ between objects and subjects all over the world in both hidden and consensual relations.

The way we relate to each other through our cameras and make sense of our recordings depends on a deeply intentional cinematographic approach that enables us to engage with our subjects as intimately as possible, while still respecting the individual’s habitus and the related cultural sensibilities. As doing visual ethnography is both a highly social endeavor as well as an aesthetic practice, which partly draws on the language from the wider cinematographic traditions (both fiction and documentary), it has one feature that seems to define it—its unscripted nature. With the camera we interpret what we perceive in the lives and environments of our subjects, through making selections in time, space and sonic landscapes, whilst we also always keep in mind that we need to show and structure a narrative (or even a non-narrative) video-production out of our recordings.

For visual ethnography, as is the case for all documentary practices, our interaction with this “unscripted nature” is prefigured by our own epistemological and methodological frameworks. In principle, all anthropology is interested in this fine line between the known and the unknown. As the most humanistic of the sciences and the most scientific of the humanities, anthropology by definition resides in these interstitial and hybrid contexts. The ethnographic sensibility is thus a very finely tuned methodological approach that attends to the whole body as a site of knowledge experience. Visual ethnography by extension attunes researchers to perceive the lived world through various audio-visual tools, which thus serve as extensions of the body — cine-eye cyborg.

From these mediated interactions we produce an original record of some particular lived reality. This material product of our recording, which we usually amass in excess, must be organized and sequenced to become sharable. This need to later edit our footage according to a certain logic demands that we also “editing in the camera” while we record. Through selections in time and space, we determine the content, but at the same time apply a ‘film-language’ that communicates a certain logic between shots in the process of building our ‘sequences’ and scenes. In recording ethnographic film, we may try to preserve the integrity of acts and interactions based on our ethnographic understanding of the internal logic of events, yet when trying to communicate an analysis of events, that integrity may become subordinate to the narrative structure of the edited film.